Chapter2 Setting Out

Approaches to the Qur’an

It would probably be better to delay this discussion for the appendices, so as not to lose many readers before even getting started, because I expect that the majority will be Muslims and that many of them find this subject upsetting. It has to do with the role of symbolism in revelation. The appendices may be more appropriate, because the main conclusions reached in this chapter will hardly be affected by these remarks, but my principle concern is with a smaller readership, which, while attempting to reconcile religion with modern thought, might be dissuaded by its own excessive literalism.

Muslims assert that the Qur’an is a revelation appropriate for all persons, times, and places, and it is not difficult to summon Qur’anic verses to support this claim. If they held to the opposite, there would not be much point in considering their scripture. In order to entertain this premise sincerely, we certainly should allow for, even anticipate, that the Qur’an would use allegory, parables, and other literary devices to reach a diverse audience. The language of the Qur’an would have to be that of the Prophet’s milieu and reflect the intellectual, religious, social, and material customs of the seventh-century Arabs. But if the essential message is universal, then it must transcend the very language and culture that was the vehicle of revelation. Since a community’s language grows with and out of its experiences, how then are realities outside that experience communicated? There appears to be only one avenue: through the employment of allegory, that is, the expression of truths through symbolic figures and actions or, as the famous Qur’an exegete Zamakhshari put it, “a parabolic illustration, by means of something which we know from our experience, of something that is beyond the reach of our perception.” 5

For example, the Qur’an informs us that Paradise in the hereafter is such that “no person knows what delights of the eye are kept hidden from them as a reward for their deeds” (32:17). Yet it also provides very sensual images of Paradise that are particularly suited to the imagination of Muhammad’s contemporaries. These descriptions recall the luxury and sensual delights of the most wealthy seventh-century Bedouin chieftains. If the reader happened to be a man from Alaska, he may be quite apathetic to these enticements. He may prefer warm sandy beaches to cool oases; sunshine to constant shade; scantily clad bathing beauties to houris, with the issue of whether or not they are virgins of no real consequence. This reader will probably take these references symbolically, reinforced by the Qur’an’s frequent assignment of the word mathal (likeness, similitude, example) to its eschatological descriptions.

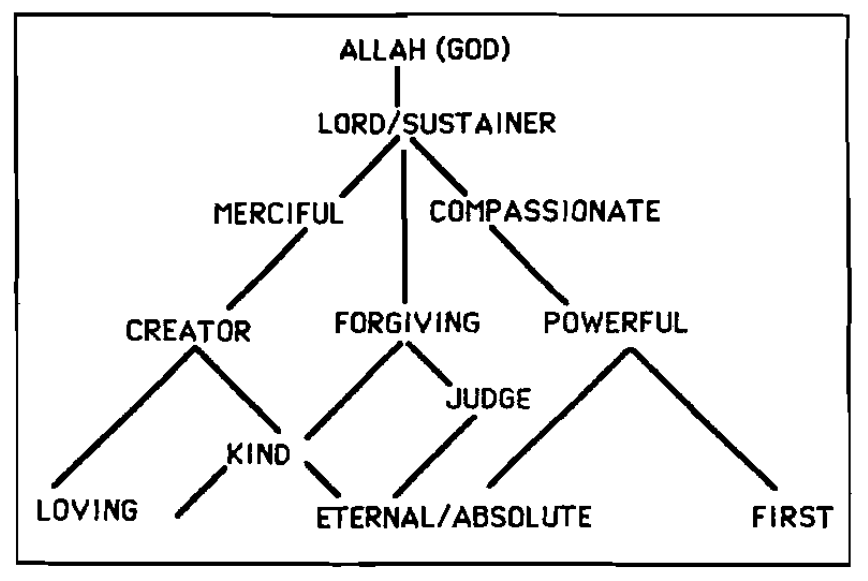

Similarly, though God is “sublimely exalted above anything that men may devise by way of definition” (6:100) and “there is nothing like unto Him” (42:11) and “nothing can be compared to Him” (112:4), the reader nonetheless needs to relate to God and His activity. Thus we find that the Qur’an provides many comparative descriptions of God. For instance, while human beings are sometimes merciful, compassionate, generous, wise and forgiving, God is The Merciful, The Compassionate, The Generous, The Wise, and The Forgiving. The Qur’an mentions God’s “face”, “hand”, “throne” and other expressions

which at first sight have an almost anthropomorphic hue, for instance, God’s “wrath” (ghadab) or “condemnation”; His “pleasure” at good deeds or “love” for His creatures; or His being “oblivious” of a sinner who was oblivious of Him; or “asking” a wrongdoer on Resurrection Day about his wrongdoing; and so forth," 6

To disallow the possibility of symbolism in such expressions would seem to imply contradictions between some statements in the Qur’an. To do so is entirely unnecessary, especially in consideration of the following key assertion:

He it is Who has bestowed upon you from on high this divine writ, containing messages clear in and of themselves (ayat muhkamat) – and these are the foundation of the divine writ – as well as others that are allegorical (mutashabihat). Now those whose hearts are given too swerving from the truth go after that pan of it which has been expressed in allegory, seeking out confusion, and seeking its final meaning, but none save God knows its final meaning. (3:7)

Therefore the Qur’an itself insists on its use of symbolism, because to describe the realm of realities beyond human perception – what the Qur’an designates as al ghayb (the unseen or imperceptible) – would be impossible otherwise. This is why it would be a mistake to insist on assigning a literal interpretation to the Qur’an’s descriptions of God’s attributes, the Day of Judgment, Heaven and Hell, etc., because the ayat mutashabihat do not fully define and explicate these, but they relate to us, due to the limitations of human thought and language, something similar. This helps explain the well-known doctrine of bila kayf (without how) of al Ash’ari, the famous tenth-century theologian whose viewpoint on this matter became dominant in Muslim thought. It states that such verses reveal truths, but we should not insist on, or ask, how these truths are realized.7

Throughout Muslim history, the literalist trend in Qur’an exegesis was one among a number of approaches. Today, in America and Canada, it has emerged as the most prevalent. It appears that the majority of Muslim lecturers in America tend to take every narrative or description in the Qur’an as a statement of a scientific or historical fact. So, for example, the story of Adam is assumed to relate the historical and scientific origins of Homo Sapiens. This tendency is reinforced by the current widespread excitement over recent Qur’an and Science studies, where many, if not most, of the discoveries of modern science are believed to have been anticipated by the Qur’an.

It is true that some of the descriptions in the Qur’an of the “signs” (ayat) in nature of God’s wisdom and beneficence bear a fascinating resemblance to certain modem discoveries, and it is also true that none of these signs can be proved to be in conflict with science. But part of the reason for this may argue against attempts by Muslims to subject the Qur’an to scientific scrutiny.8 The Qur’an is very far from being a science textbook. Its language is of the highest literary quality and open to many different shades of meaning. The descriptions of many of the Qur’an’s signs that are believed today to predict recently established facts appear to be consistently and intentionally ambiguous, avoiding a degree of explicitness that would conflict with any reader’s level of knowledge of whatever era. If the Qur’an contained a precise elaboration of these phenomena (the big bang theory, the splitting of the atom, the expansion of the universe, to name a few), these would have been known to ancient Muslim scientists. A truly wondrous feature of the Qur’an is that these signs lose nothing of their power, beauty, and mystery from one generation to the next; each generation has found them compatible with the current state of knowledge. To be inspired with awe and wonder by the Qur’anic signs is one thing; to attempt to deduce or impose upon them scientific theories is another and, moreover, is contrary to the Qur’an’s style.

The relationship between the Qur’an and history is very much the same. Anyone familiar with the Bible will notice that there are many narratives in the Qur’an that have Biblical parallels. In the past, Orientalists would accuse Muhammad, whom they assumed to be the Qur’an’s author, of plagiarizing or borrowing material from Jewish and Christian sources. This opinion has become increasingly unpopular among western scholars of Islam. For one thing, where Biblical parallels do exist, the Qur’anic accounts almost always involve many key differences in detail and meaning. Equally important is the fact that the Qur’an itself assumes that its initial hearers were fairly well acquainted with these tales. It is therefore very probable that through centuries of contact, Jews, Christians, and pagans of the Arabian peninsula adopted, with modifications, each other’s oral traditions. It also would not be at all surprising that traditions shared by Jews and Arabs of the Middle East would go back to a common source, since they shared a common ancestry. Hence, the conjecture that the Qur’an borrows from the Bible is inappropriate.

In addition to biblical parallels, the Qur’an contains a number of stories that were apparently known only to the Arabian peninsula and at least one of mysterious origins.9 A striking difference between all of the Qur’anic accounts and the biblical narratives is that while the latter are very often presented in a historical setting, the former defy all attempts to do so, unless outside sources are consulted. In other words, relying exclusively on the Qur’an, it is nearly impossible to place these stories in history. The episodes are told in such a way that the meaning behind the story is emphasized while extraneous details are omitted. Thus, western readers who know nothing of the Arabian tribes of ’Ad and Thamud readily understand the moral behind their tales. This omission of historical detail adds to the transcendent and universal appeal of the narratives, for it helps the reader focus on the timeless meaning of the stories.

The Qur’anic stories are so utterly devoid of historical reference points that it is not always clear whether a given account is meant to be taken as history, a parable, or an allegory. Consider the following two verses from the story of Adam:

It is We Who created you, then We gave you shape, then We bade the angels, “Bow down to Adam!” and they bowed down; not so Iblis; he refused to be of those who bow down. (7:11)

And when your Lord drew forth from the children of Adam, from their loins, their seed, and made them testify of themselves, (saying) “Am I not your Lord?” They said, “Yes, truly we testify.” (That was) lest you should say on the Day of Resurrection: “Lo! of this we were unaware.” (7:172)

Note the transition in 7:11 from “you” (plural in Arabic) in the first two clauses to “Adam” in the third, as if mankind is being identified with Adam. These verses seem to demand symbolic interpretations, otherwise from the first we would have to conclude that we were created, then we were given shape, then the command was given concerning the first man! As for 7:172, I would not even know how to begin to interpret this verse concretely, and it should come as no surprise that many ancient commentators also understood it symbolically.

The Qur’an’s eighteenth surah, al Kahf, relates a number of beautiful stories in an almost surrealistic style. For example, verse 86, from the tale of Dhul Qarnain reads,

Until, when he reached the setting of the sun, and he found it setting in a muddy spring, and found a people near it. We said: “O Dhul Qarnain! Either punish them or treat them with kindness.” (18:86)

This verse has puzzled Muslim commentators, many of whom searched history for a great prophet conqueror that might compare to Dhul Qarnain, who reached the lands where the sun rises and sets. The most popular choice was Alexander the Great, which is patently false since he is well known to have been a pagan. Since the sun does not literally set in a muddy spring with people nearby, a less-than-literal interpretation is forced upon us.

Rather than belabor the point, let me summarize my position. On the basis of the style and character of the Qur’an, I believe that the most general and most cautious statement one can make is: The Qur’an relates many stories, versions with which the Arabs were apparently somewhat familiar, not for the sake of relating history or satisfying human curiosity, but to “draw a moral, illustrate a point, sharpen the focus of attention, and to reinforce the basic message.”10 I would advise against attempts to force or decide the historicity of each of these stories. First of all, because the Qur’an avoids historical landmarks and since certain passages in some narratives clearly can not be taken literally, such an insistence seems unwarranted. Furthermore, imposing such limitations on the Qur’an may lead, unnecessarily, to rational conflicts and obstructions that distract the reader from the moral of a given tale. The Qur’an itself harshly criticizes this inclination in Surat al Kahf:

Some say they were three, the dog being the fourth among them. Others say they were five, the dog being the sixth – doubtfully guessing at the unknown. Yet others say seven, the dog being the eighth. Say, “My Lord knows best their number, and none knows them, but a few. Therefore, do not enter into controversies concerning them, except on a matter that is clear.” (18:22)

Moreover, it would be humanly impossible to definitively decide the historic or symbolic character of every tale; no one has the requisite level of knowledge of history and Arab oral tradition – not to mention insight into the intent and wisdom of the author – to make such a claim. Personal ignorance should be admitted, but it should not be allowed to place limits and bounds on the ways and means of revelation.

As we set out on our journey, we will be approaching the Qur’an from the standpoint of meaning; seeking to make sense of and find purpose in the existence of God, man, and life. We are now ready to embark. We have made our preparations and have broken camp. With the Qur’an before us, we enter the first page.

An Answer to a Prayer

In the Name of God, The Merciful, The Compassionate 1. Praise be to God, Lord of the worlds; 2. The Merciful, The Compassionate; 3. Master of the day of Requital; 4. You do we serve and You do we beseech for help; 5. Guide us on the straight path; 6. The path of those whom you have favored; 7. Not those upon whom is wrath and not those who are lost. (1:1-7)

Volumes upon volumes have been written on the Qur’an’s opening surah, even though it consists of only seven short verses, but we, my fellow travelers, have only time enough to pause for a few very brief observations.

The first verse indicates a hymn of praise, to God, “the Lord of the worlds”. The divine names, “The Merciful, The Compassionate”, appearing in the second, head every surah but one (the ninth) and are among the most frequently mentioned attributes of God, both in the Qur’an and by Muslims in their everyday speech. The mood abruptly changes in verse two as it reawakens deep-seated anxieties and conflicts. No sooner are God’s mercy and compassion emphasized than we are threatened with the “Day of Requital”. Would it not have been more tactful to postpone such considerations, to wait until the reader is a little more comfortable with and confident in the Qur’an? Assertions about God’s mercy, compassion, gentleness, or love never drove us from religion, but warnings of a Day of Judgment, of Hell, of eternal damnation that we found impossible to harmonize with mercy and compassion, did.

The fourth verse goes even deeper into the quagmire as it reminds us that service is rendered and pleas for help are directed to the very creator of the predicament from which we seek salvation. Far from allowing us to warm up to its message, the scripture wastes no time recalling our complaints against religion. We will discover that this is a persistent tactic of the Qur’an; that it repeatedly agitates the skeptic by confronting him with his personal objections. We will soon see that this Qur’an is no soft sell nor hard sell; that in reality it is no sell at all; that it is no less than a challenge, a dare, to fight and argue against this book.

We can relate to the last three verses all too readily. Life is a chaotic puzzle, a random and confusing maze of paths and choices that lead no where but to broken dreams, empty accomplishments, unfulfilled expectations, one mirage after another. Is there a right path, or are all in the end equally meaningless? Note the transition from personal to impersonal in verses six and seven, as if to say that to obtain the “straight path” is a divine favor conferred on those who seek and heed divine guidance and that those who do not follow divine guidance are exposed to all of life’s impersonal, unfeeling wrath, and utter loss and delusion. This wrath and loss we know well, for we have absorbed life’s anger and aimlessness and made it our own; it is our argument for the nonexistence of a personal God and the foundation of our philosophy.

We moved through the seven verses quickly. There was a subtle shift in mood from the first four that glorified God to the last three that asked for guidance. More than likely our first reading of them was so casual that we did not observe the change. It was not until we had finished the opening surah that we realized that we had just involuntarily and semiconsciously made a supplication. We were almost tricked into it before we had a chance to resist. The beginning of the next surah will inform us that whether we consciously intended it or not, our prayer has reached its destination and that it is about to receive an answer.

That Is the Book

In the name of God, the Merciful, The Compassionate 1. Alif lam mim 2. That is the book, wherein no doubt, is guidance to those who have fear, 3. Who believe in the unseen, and are steadfast in prayer and spend out of what We have given them, 4. And who believe in that which is revealed to you and that which was revealed before you, and are certain of the hereafter. 5. These are on guidance from their Lord, and these, they are the successful. (2:1-5) 11

Alif lam mim is a transliteration of the three Arabic letters that open this surah. Twenty-nine surahs begin with such letter combinations of the Arabic alphabet. They continue to be a mystery to Qur’an commentators, and opinions differ as to their meaning. Most believe they are abbreviations of words or mystic symbols, but we will leave such speculation aside.

The second verse declares to us that that book, the Qur’an – that we have before us – is without doubt the answer to the prayer we had just recited. The tenor of the Qur’an from here on is different from that of the opening surah. In the first surah, it was the reader humbly petitioning God for guidance, while the perspective of the remainder of the Qur’an, as this verse insists, will be God, in all His supreme power and grandeur, proclaiming to the reader the guidance that he sought, whether consciously or unconsciously, knowingly or unknowingly. Also observe that doubt and fear are accentuated in this verse. We should not exclude ourselves so hastily from these attributes, even though we do not fit the full description continued in verses three through five. We do have doubts, not only about God’s existence but also about our denial of it. If we were absolutely certain of our atheism, we would not be reading this scripture. As much as we hate to admit it, we are not quite sure of ourselves; there exists in us at least a glimmer of doubt – and of fear. The word muttaqin, translated as “those who have fear”, comes from the Arabic root which means to protect, to guard, to defend, to be cautious. It implies an acute alertness to one’s potential weaknesses, a person on his toes, a self-critical awareness. We may not be believers, but we are definitely guarded, defensive and cautious when it comes to religion, otherwise we would not be atheists; we would have simply accepted what we inherited from our parents. These are the same qualities that brought us to this journey, because we suspect that we might be wrong, that there is at least a chance that there is a God and if there is, then we are ignoring what would have to be the most important fact in our being.

Verse two also begins a description of the Qur’an’s potential audience. Like many a book of knowledge, it describes the prerequisites and predisposition necessary to fully benefit from its contents. The most sincere in their belief in God (2:2-5) will profit the most. They believe in realities beyond their perceptions and are devout and are kind to their fellow man. They have faith in what is currently being revealed to them, which are the same essential truths of all ages.

Verse six refers to the rejecters, who refuse to even consider the Qur’an. The Qur’an in turn promptly dismisses them in the next verse. Verse eight begins a relatively lengthy discussion (2:8-20) of all those in between, who waver between belief and disbelief, often distracted and blinded by worldly pursuits. From the standpoint of the Qur’an, we may be towards the boundary of this category. Verses twenty through twenty-nine outline some of the Qur’an’s major themes: Man’s need to serve the one God, the prophethood of Muhammad, the hereafter and final judgment, the Qur’an’s use of symbolism (2:26), the resurrection of man, and God’s ultimate sovereignty.

Verse thirty begins the story of man. We will proceed slowly here, line by line, since this has a strong bearing on our questions. The ancient Qur’anic commentators would endorse such an approach, for they used to speak of the ijaz of the scripture – its inimitable eloquence that combines the most beautiful and yet most economical expression. They would advise us not to rush hastily, but to allow each verse, each word, each sound, to penetrate our hearts and minds in order to reap its greatest possible benefit. Otherwise, we may deprive ourselves of essential keys to unlocking truths buried deep within us.

Behold, your Lord said to the angels: “I am going to place a vicegerent on earth.” They said: “Will you place therein one who will spread corruption and shed blood? While we celebrate your praises and glorify your holiness?” He said: “Truly, I know what you do not know.” (2:30)

The opening scene is heaven as God informs the angels that He is about to place man on earth. Adam, the first man, has not yet appeared. From the verses that follow, it is clear that at this point in the story Adam is free of any wrongdoing. Nevertheless, God plans to place him (and his descendants 6:165; 27:62; 35:39) on earth in the role of vicegerent or vicar (khalifah). There is no insinuation here that earthly life is to serve as a punishment. The word khalifah means “a vicar”, “a delegate”, “a representative”, “a person authorized to act for others”. Therefore, it appears that man is meant to represent and act on behalf of God in some sense.

The angels’ reply is both fascinating and disturbing. In essence it asks, “Why create and place on earth one who has it within his nature to corrupt and commit terrible crimes? Why create this being, who will be the cause and recipient of great suffering?” It is obvious that the angels are referring here to the very nature of mankind, since Adam, in the Qur’an, turns out to be one of God’s elect and not guilty of any major crime. The question is made all the more significant when we consider who and from where it comes.

When we think of angels, we imagine peaceful, pure, and holy creatures in perfect and joyous submission to God. They represent the model to which we should aspire. In our daily speech, we reserve the word “angel” for the noblest of our species. Mother Theresa is often called an “angel of mercy” by the press. Of a person who does something very kind we say, “He is such an angel!” When my wife and I look in on our daughters at night, sleeping so beautifully and serenely, we remark to each other, “Aren’t they angels?” Our image of an angel is of the perfect human being. This is what gives the angels’ question such force, for it asks: “Why create this patently corrupt and flawed being when it is within Your power to create us?” Thus they say: “While we celebrate your praises and glorify your holiness?” Their question is given further amplification by the fact that it originates in heaven, for what possible purpose could be served by placing man in an environment where he could exercise freely his worst criminal inclinations? All of these considerations culminate in the obvious objection: Why not place man with a suitable nature in heaven from the start? We are not even a single verse into the story of man and we have already confronted our (the atheists’) main complaint. And, it is put in the mouths of the angels!

The verse ends not with an explanation, but a reminder of God’s superior knowledge, and hence, the implication that man’s earthly life is part of a grand design. Many western scholars have remarked that the statement, “I know what you do not know,” merely dismisses the angel’s question. However, as the sequence of passages will show, this is not the case at all.

Our initial encounter with the Qur’an has been anything but pleasant; it has been distressful and irritating. Either the author is completely unaware of possible philosophical problems and objections, or else he is deliberately provoking us with them! We are a mere thirty-seven verses into the Qur’an and our anxiety and resentment has been aroused to a fever pitch. We ask, “Why indeed subject mankind to earthly suffering? Why not remove us to heaven or place us there from the first? Why must we struggle to survive? Why create us so vulnerable and self-destructive? Why must we suffer broken hearts and broken dreams, lost loves and lost youth, crises and catastrophes? Why must we experience pains of birth and pains of death? Why?” we beg in our frustration. “Why?” we plead in all our sorrow and emptiness. “Why?” we insist in our anguish. “Why?!” we scream out to the heavens. “Why?!” we plead with the angels. “If You are there and You hear us, tell us, why create man?!!”

And His Lord Turned toward Him

We move now to verse thirty-one, where we find that the Qur’an continues to explore the angels’ question.

And He taught Adam the names of all things; then He placed them before the angels, and said, “Tell me their names if you are right.” (2:31)

Clearly, the angels’ question is being addressed in this verse. Adam’s capacities for learning and acquiring knowledge, his ability to be taught, are the focus of this initial response. The next verse demonstrates the angels’ inferiority in this respect. Special emphasis is placed on man’s ability to name, to represent by verbal symbols, “all things” that enter his conscious mind: all his thoughts, fears, and hopes, in short, all that he can perceive or conceive. This allows man to communicate his experience and knowledge on a relatively high level, as compared to the other creatures about him, and gives all human learning a preeminent cumulative quality. In several places in the Qur’an, this gift to mankind is singled out as one of the greatest bounties bestowed on him by God.12

They said: Glory to you: we have no knowledge except what You taught us, in truth it is you who are the Knowing, the Wise. (2:32)

In this verse, the angels plead their inability to perform such a task, for, as they plainly state, it would demand a knowledge and wisdom beyond their capacity. They maintain that its performance would, of course, be easy for God, since His knowledge and wisdom is supreme, but that the same could not be expected of them. In the next passage, we discover that Adam possesses the level of intelligence necessary to accomplish the task and hence, though his knowledge and wisdom are less than God’s, it is yet greater than the angels.

He said: “O Adam! Tell them their names.” When he had told them their names, God said: “Did I not tell you that I know what is unseen in the heavens and the earth and I know what you reveal and conceal?” (2:33)

Here we have an emphatic statement that man’s greater intellect figures into an answer to the angels’ question. We are informed that God takes all into account, in particular, all aspects of the human personality: man’s potential for evil, which the angels’ question “reveals”, and his complementary and related capacity for moral and intellectual growth, which their question “conceals”. To drive home this point, the next verse has the angels demonstrate their inferiority to Adam and shows that man’s more complex personality makes him a potentially superior being.

And behold, We said to the angels, “Bow down to Adam” and they bowed down. Not so Iblis: he refused and was proud: he was of the rejecters. (2:34)

We also find in this verse the birth of sin and temptation. The Qur’an later informs us that Iblis (Satan) is of the jinn (18:50), a being created of a smokeless fire (55:15) and who is insulted at the suggestion that he should humble himself before a creature made of “putrid clay” (7:12; 17:61; 38:76). Satan is portrayed as possessing a fiery, consuming, and destructive nature. He allows his passions to explode out of control and initiates a pernicious rampage. We are often told that money is at the root of all evil, but here the lesson appears to be that pride and self-centeredness is at its core. Indeed, many terrible wrongs are committed for no apparent material motive.

And we said: “O Adam! Dwell you and your spouse in the garden and eat freely there of what you wish, but come not near this tree for you will be among the wrongdoers.” (2:35)

Thus the famous and fateful command. Yet, the tone of it seems curiously restrained. There is no suggestion that the tree is in any way special; it almost seems as if it were picked at random. Satan will later tempt Adam with the promise of eternal life and “a kingdom that never decays” (20:121), but this turns out to be a complete fabrication on his part. There is not the slightest hint that God is somehow threatened at the prospect of Adam and his spouse violating the command; instead, He voices concern for them, because then “they will be among the wrongdoers”.

This is probably an appropriate place to reflect on what we have learned so far. We saw how God originally intended for man to have an earthly life. We then observed a period of preparation during which man is “taught” to use his intellectual gifts. Now, Adam and his spouse are presented a choice, of apparently no great consequence, except for the fact that it is made to be a moral choice. It thus seems that man has gradually become – or is about to become – a moral being.

But Satan caused them to slip and expelled them from the state in which they were. And we said: "Go you all down, some of you being the enemies of others, and on earth will be your dwelling place and provision for a time. (2:36)

Once again the Qur’an seems to have a penchant for understating things. The Arabic verb azalla means to cause someone to unintentionally slip or lose his footing. But how can one of the most terrible wrongs ever committed be described as a momentary “slip”? Yet perhaps we are letting our own religious backgrounds, even though we rejected them, distort our reading. Perhaps the Qur’an considers this sin as nothing more than a temporary slip. After all, it is only a tree! Its only significance may be that it signals a new stage in man’s development, that it causes man to depart from a previous state.

The words “some of you being the enemies of others” apparently refer to all mankind and echo the angels’ remark concerning man’s earthly strife.

Under normal circumstances, we would know now what to expect. We have been terrified by it ever since we were children. It shook us from our sleep and required our mothers to calm our fears and, unlike other nightmares, it never went away when we awoke, because it was confirmed by everyone we trusted. We know that there is about to be unleashed on mankind a rage, a violence, a terror, the like of which has never been known either before or since. Like a huge, thundering, black, and terrifying storm cloud, looming on the horizon and heading straight for us, mankind is about to be engulfed by an awesome fury. And when the smoke clears, man will find himself sentenced, TO LIFE, on earth, where he and all his descendants will suffer and struggle to survive by their sweat and toil. There they will experience illness, agony, and death. There they will suffer endless pain and torment and, in all probability, more of the same and worse in the life to come.

And the WOMAN!!!! To her belong the greater punishment and humiliation, for it was she who duped Adam with her beauty and her charms. It was she who allied herself with Satan – an alliance for which Adam was, of course, no match. It was she who corrupted his innocence and exposed his weaknesses. So it is she who will ache and bleed monthly. It is she who will scream out in her labor pains. It is she who will bare the brunt of greater humiliation and drudgery, because the man will be made to rule over her, in spite of the fact that he is obviously her intellectual inferior, since he was unequal to her cleverness and guile.

So we wince and shudder as we turn to the terror we have always known. We cringe and cower as we peek to the next verse.

Then Adam received words from his Lord, and He turned to him (mercifully). Truly He is Oft-returning, the Merciful. (2:37)

What is this? What is this talk of mercy and turning compassionately towards man? Where is the passion, the jealousy, the anger, erupting out of control?

In this verse, those that follow, and others in the Qur’an that relate the same episode (see, for example,20:116-124, the tone is first and foremost consoling and assuring. God immediately pardons Adam and Eve, with no greater blame assigned to either of them. Adam receives “words”, which some commentators interpret to be words of inspiration and others see as divine assurances and promises. The next verse supports the latter viewpoint, while there are others that include him in the community of prophets (for example, 3:32) which sustain the first.

We said: Go down from this state all of you together; and truly there will come to you guidance from Me and whoever follows My guidance, no fear shall come upon them, nor shall they grieve. (2:38)

The command issued in 2:36 is repeated here, but this time with special emphasis put on God’s assurances and promises to mankind, thus further precluding the interpretation that man’s earthly life is a punishment. This explains why the Qur’an has man remain on earth even though Adam and Eve are immediately forgiven. Nonetheless, the Qur’an will insist, as we read through it, that life serves definite aims and, as the next verse warns, it has grave consequences and must be taken seriously.

But those who are rejecters and give the lie to our signs, these are the companions of the fire: they will abide in it. (2:39)

The story of Adam ends here to be taken up in bits and pieces later. Many questions and problems have been raised, but we have obtained only some clues and clarifications. This is another characteristic of the Qur’an: It interweaves themes throughout the text, rather than provide several distinct and complete discourses on various topics. In this way it baits the reader, luring him or her into its design, so that its different approaches are allowed to exert their influence frequently and repeatedly. It would be naive of us to expect long uninterrupted dissertations on metaphysics or theology, for such would be understandable to few and of interest and inspiration to far fewer. On the other hand, if the Qur’an is a guidance, as it claims to be, then we should anticipate suggestions, guideposts, and touchstones that help us along the way. Be assured, the Qur’an will not simply translate us to our goal; it will provide directions at different stages, but the traveling and the discovery will have to be ours, because the questions we ask are not only about God – they are about ourselves as peculiar individuals and we are the only persons who have real access to our souls. Thus, as the Qur’an might say, we must be willing not only to search the horizons, but also our own selves, until we know as much as we can grasp of the truth (41:53).

“When Will God’s Help Come?”

Although the picture is still far from clear, some themes that invite further reflection and elaboration have emerged. The most striking fact that we observed is that the Qur’an does not maintain that life on earth is a punishment. Long before Adam and Eve enter the story, the angels raise the troublesome question: Why create man? A series of verses supplies pieces of an answer. Man has a relatively higher intelligence than other creatures. His nature is more complex and he has a greater degree of personal freedom. Thus, he has not only potential for growth in evil but, reciprocally, he has the potential for growth in virtue. We witness a period of preparation, wherein man learns to use his intellectual strengths. Adam and Eve are then ready to become moral beings. They are presented with a somewhat innocuous – although from the standpoint of their development critical – moral choice. They slip and enter a moral phase in their existence, which is symbolized in other Qur’anic passages that have the couple now conscious of sexual morality and modesty (7:19-25; 20:120-123). Thus they depart from a state of ignorance, innocence, and bliss. Man’s higher intellect, freedom of choice, and growth potential will inevitably involve him in conflict and travail. The last of these is the focus of the angels’ question. As we continue along our journey, the Qur’an will stress repeatedly these three features of the human venture: reasoning, choice, and adversity. We will consider each separately.

Reason

That the Qur’an gives a prominent place to reason in the attainment of faith is well known and frequently mentioned by western Islamicists. Many western scholars view this as a defect, because they see faith and reason as being inherently incompatible. For example, H. Lammens sarcastically states that the Qur’an “is not far from considering unbelief as an infirmity of the human mind!” 13 His reaction, however, is more cultural and emotional than rational, having its roots in the West’s own struggle with religion and reason. Yet not all western scholars are so cynical. While certainly no advocate for Islam, Maxime Rodinson sees this aspect of the Qur’an as somewhat in its favor and writes:

The Koran continually expounds the rational proofs of Allah’s omnipotence: the wonders of creation, such as the gestation of animals, the movements of the heavenly bodies, atmospheric phenomena, the variety of animal and vegetable life so marvelously well adapted to men’s needs. All those things “are signs (ayat) for those of insight” (3:187-190) …. Repeated about fifty times in the Koran is the verb ’aqala which means “connect ideas together, reason, understand an intellectual argument”. Thirteen times we come upon the refrain, after a piece of reasoning: a fa-la ta’qilun “have ye then no sense?” (2:41-44, etc.) The infidels, those who remain insensible to Muhammad’s preaching, are stigmatized as “a people of no intelligence,” persons incapable of the intellectual effort needed to cast off routine thinking (5:63-58, 5:102-103; 10:42-43; 22:45-46; 9:14). In this respect they are like cattle (2:166-171; 5:44-46). 14

The Qur’an insists that it contains signs for those who are “wise” (2:269), “knowledgeable” (29:42-43), “endowed with insight” (39:9), and “reflective” (45:13). Its persistent complaint against its rejecters is that they refuse to make use of their intellectual faculties and that they close their minds to learning. The Qur’an asks almost incredulously: “Do they not travel through the land, so that their hearts may thus learn wisdom?” (22:44), “Do they not examine the earth?” (26:7), “Do they not travel through the earth and see what was the end of those before them?” (30:9), “Do they not look at the sky above them?” (50:6), “Do they not look at the camels, how they are made?” (88:17), “Have you not watched the seeds which you sow?” (56:63).

Muslim school children throughout the world are frequently reminded of the first five verses of the ninety-sixth surah:

Read in the name of your Lord, who has created – created man out of a tiny creature that clings! Read and your Lord is the Most Bountiful One, who has taught the use of the pen, taught man what he did not know. (96:1-5)

These verses are believed to comprise Muhammad’s very first revelation. “Read!” It commands, as the skill of written communication is presented as one of the great gifts to mankind, because it is by use of the pen that God has taught man what he did not or could not know. Here again, the Qur’an highlights man’s unique ability to communicate – this time in writing – and to collectively learn from the insights and experiences of others.

Repetition is indicative of the importance given to certain topics. It should be observed that the Arabic word for knowledge, ’ilm, and its derivatives appear 854 times in the Qur’an, placing it among the most frequently occurring words. It should also be noted that in many of its stories, where the Qur’an presents a debate between a believer and disbeliever, the believer’s stance is inevitably more rational and logical than his opponent’s.

Choice

The Qur’an presents human history as a perennial struggle between two opposing choices: to resist or to surrender oneself to God. It is in this conflict that the scripture immerses itself and the reader; it could be said to be the very crux of its calling. This choice must be completely voluntary, for the Qur’an demands, “Let there be no compulsion in religion – the right way is henceforth clearly distinct from error” (2:256). The crucial point is not that one should come to know and worship God, but that one should freely choose to know and worship God. Thus we find the repeated declaration that God could have made all mankind rightly guided, but it was within His purposes to do otherwise.

Had He willed He could indeed have guided all of you. (6:149)

Do not the believers know that, had God willed, He could have guided all mankind? (13:31)

And if We had so willed, We could have given every soul its guidance. (32:13)

Had God willed He could have made you all one community. But that He may try you by that which He has given you. So vie with one another in good works. Unto God you will all return, and He will inform you of that wherein you differ. (5:48)

The Qur’an categorically affirms that God is not diminished nor threatened by our choices, yet they do carry grave consequences for the individual, as the primary beneficiary of a good deed and the primary casualty of an evil act is the doer.

Enlightenment has come from your God; he who sees does so to his own good, he who is blind is so to his own hurt. (6:104)

Indeed they will have squandered their own selves, and all their false imagery will have forsaken them. (7:53)

And they did no harm against Us, but [only] against their own selves did they sin. (7:160)

And so it was not God who wronged them, it was they who wronged themselves. (9:70)

And whosoever is guided, is only (guided) to his own gain, and if any stray, say: “I am only a warner.” (27:92)

And if any strive, they do so for their own selves: For God is free of all need from creation. (29:6)

We have revealed to you the book with the truth for mankind. He who lets himself be guided does so to his own good; he who goes astray does so to his own hurt. (39:41) (Also see (10:108; 17:15; 27:92).)

These statements are hardly easy on the reader. At first glance they seem to indicate a detachment from and indifference to man’s situation. Philosophically, such a stance may be consistent with God’s transcendence, but only at the expense of attempting any possible relationship with God. Yet such an interpretation would be inappropriately severe. The Qur’anic God is anything but impartial to mankind’s condition. He sends prophets, answers prayers (2:186; 3:195), and intervenes in and manipulates the human drama, as in the Battle of Badr (3:13; 8:5-19; 8:42-48). All is under His authority, and nothing takes place without His allowing it (4:78-79).

The Qur’an’s “most beautiful names” of God imply an intense involvement in the human venture. These names, such as The Merciful, The Compassionate, The Forgiving, The Giving, The Loving, The Creator, etc., reveal a God that creates men and women in order to relate to them on an intensely personal level, on a level higher than with the other creatures known to mankind, not out of a psychological or emotional need but because this is the very essence of His nature. Therefore, we find that the relationship between the sincere believer and God is characterized consistently as a bond of love. God loves the good-doers (2:195; 3:134; 3:148; 5:13; 5:93), the repentant (2:222), those that purify themselves (2:222; 9:108, the God-conscious 3:76; 9:4; 9:7), the patient (3:146), those that put their trust in Him (3:159), the just (5:42; 49:9; 60:8), and those who fight in His cause (61:4). And they, in turn, love God.

Yet there are men who take others besides God as equal (with God), loving them as they should love God. But those who believe love God more ardently. (2:165)

Say: "If you love God, follow me, and God will love you, and forgive you your faults; for God is The Forgiving, The Merciful. (3:31)

O you who believe! If any from among you should turn back from his faith, then God will assuredly bring a people He loves and who love Him. (5:54)

On the other hand, tyrants, aggressors, the corrupt ones, the guilty, rejecters of faith, evil-doers, the arrogant ones, transgressors, the prodigal, the treacherous, and the unjust will not experience this relationship of love (2:190; 2:205; 2:276; 3:32; 3:57; 3:140; 4:36; 4:107; 5:64; 5:87; 6:141; 7:31; 7:55; 8:58; 16:23; 22:38; 28:76; 8:77; 30:45; 31:18; 42:40; 57:23).

There are Muslim and non-Muslim scholars who view God in the Qur’an as virtually indifferent to humanity, establishing the cosmos with fixed laws of cause and effect in all spheres (physical, psychological, spiritual, etc.), and then setting it to run subject to them. Others have seen Him as so completely involved in and in control of creation that all is totally determined, even our choices. Many believe that shades of both viewpoints are present and that they may be irreconcilable. The latter is perhaps closest to the truth, although the irreconcilability is not necessary. Certainly, the Qur’an maintains God’s absolute sway over all creation, which He ceaselessly and continuously sustains, maintains, and influences. Nothing exists or takes place without His permission. Yet He empowers us with the ability to make choices, act them out, and see them, most often, to their expected conclusions. In fact, He frequently leads us to such critical choices. In particular, He allows and enables us to make decisions that are detrimental to ourselves and others:

Say: “All things are from God.” But what has come to these people, that they fail to understand a single fact? Whatever good befalls you is from God, but whatever evil befalls you, is from yourself. (4:78-79)

The assertion here is that our ability to experience true benefit or harm comes from God, but to do real injury to ourselves, in an ultimate and spiritual sense, depends on our actions and decisions, which God has empowered us to make.

As noted above, our acts and choices in no way threaten God and it is the individual who gains or loses by them. However, on the collective level, the Qur’an shows that God intends to produce through this earthly experience persons that share a bond of love with Him. While any individual may or may not pursue this, the Qur’an acknowledges that there will definitely be people who will, and their development is apparently the very object of man’s earthly life (15:39-43; 17:64-65).

Our vision is still quite blurry, but it seems somehow a little clearer than when we started, although we still have far to go. Questions persist about the need for this earthly life as well as the roles of human choice, intelligence, and suffering in the creation of individuals. It also feels as if we are slipping into the difficult topic of predestination. We will reserve that subject for the end of this chapter, for it will take us too far afield at this stage. However, we need to discuss one more Qur’anic statement that relates to divine and human will, because it is very often misunderstood and has a strong bearing on the theme of human choice.

The Qur’an frequently states that God “allows to stray whom He will, and guides whom He will” (2:26; 4:88; 4:143; 6:39; 7:178; 7:186; 3:27; 14:4; 16:93; 35:8; 39:23; 39:36; 40:33; 74:31). This phrase is typically rendered in most English interpretations as “God misleads whom He will, and guides whom He will”. Grammatically, both renderings are possible, because the verb adalla could be used in either sense. It could mean either “to let someone or something stray unguided”, or equally, “to make someone or something lose his/its way”. Ignaz Goldziher, the famous Orientalist and scholar of Arabic, strongly argues in favor of the first rendition. He writes,

Such statements do not mean that God directly leads the latter into error. The decisive verb (adalla) is not, in this context, to be understood as “lead astray”, but rather as “allow to go astray”, that is, not to care about someone, not to show him the way out of his predicament “We let them (nadharuhum) stray in disobedience” (6:110). We must imagine a solitary traveler in the desert: that image stands behind the Qur’an’s manner of speaking about guidance and error. The traveler wanders, drifts in limitless space, on the watch for his true destination and goal. Such a traveler is man on the journey of life. 15

His observation is given further support by the fact that almost all of the statements in the Qur’an of this nature are immediately preceded or followed by others that assert that God guides or refuses to guide someone according to his/her choices and predisposition. We find that “God does not guide the unjust ones”, “God does not guide the transgressors”, and God guides aright those who “listen”, are “sincere”, and are “God-conscious” (2:26, 2:258, 2:264; 3:86; 5:16, 5:51, 5:67, 5:108; 6:88, 6:144; 9:19, 9:21, 9:37, 9:80, 9:109; 12:52; 3:27; 16:37, 16:107; 28:50; 39:3; 40:28; 42:13; 46:10; 47:8; 61:7; 62:5; 3:6). Thus we find that “when they went crooked, God bent their hearts crooked” (61:5). This demonstrates that receiving or not receiving guidance is affected by sincerity, disposition and willingness; it recalls the saying of Muhammad: “When you approach God by an arm’s length, He approaches you by two, and if you come to Him walking, He comes to you running.” 16 Therefore, the phrase “God allows to stray whom He wills” illumines what we have already concluded: while God, according to the Qur’an, could guide all mankind uniformly, He has other purposes and hence does not. Instead, He has created man with a unique and profound ability to make moral decisions and He monitors, influences, and guides each individual’s moral and spiritual development in accordance with them.

Suffering

The great divide between theist and atheist is their reactions to human suffering. Often the first views it as either deserved or an impenetrable mystery, while the second sees it as unnecessary and inexcusable. The Qur’an advocates neither viewpoint. Trial and tribulation are held to be inevitable and essential to human development and both the believer and unbeliever will experience them.

Most assuredly We will try you with something of danger, and hunger, and the loss of worldly goods, of lives and the fruits of your labor. But give glad tidings to those who are patient in adversity – who when calamity befalls them, say, "Truly unto God do we belong and truly, unto him we shall return. (2:155)

Do you think that you could enter paradise without having suffered like those who passed away before you? Misfortune and hardship befell them, and so shaken were they that the Messenger and the believers with him, would exclaim, “When will God’s help come?” Oh truly, God’s help is always near. (2:214)

You will certainly be tried in your possessions and yourselves. (3:186)

And if we make man taste mercy from Us, then withdraw it from him, he is surely despairing, ungrateful. And if we make him taste a favor after distress has afflicted him, he says: The evils are gone away from me. Truly he is exultant, boastful; except those who are persevering and do good. For them is forgiveness and a great reward. (11:9-11)

Every soul must taste of death. And we try you with calamity and prosperity, [both] as a means of trial. And to Us you are returned. (21:35)

O man! Truly you’ve been toiling towards your Lord in painful toil – but you shall meet Him! (84:6)

Man, however, does not grow only through patient suffering, but also by striving and struggling against hardship and adversity. This explains why jihad is such a key concept in the Qur’an. Often translated as “holy war”, the word jihad literally means “a struggle”, “a striving”, “an exertion”, or “a great effort”. It may include fighting for a just cause, but it has a more general connotation as the associated verbal noun of jahada, “to toil”, “to weary”, “to struggle”, “to strive after”, “to exert oneself”. The following verses, revealed in Makkah before Muslims were involved in combat, bring out this more general sense.

And those who strive hard (jahadu) for Us, We shall certainly guide them in Our ways, and God is surely with the doers of good. (29:69)

And whoever strives hard (jahada) strives (yujahidu) for his self, for God is Self-Sufficient, above the need of the worlds. (29:6)

And strive hard (jahidu) for God with due striving (jihadihi). (22:78)

So obey not the unbelievers and strive against them (jahidhum) a mighty striving (jihadan) with it [the Qur’an]. (25:52)

The last verse occurs in a passage that encourages Muslims to make use of the Qur’an when they argue with disbelievers.

The Qur’an’s attitude towards suffering and adversity is not passive and resigned, but positive and dynamic. The believers are told that they will surely suffer and to be patient and persevering in times of hardship, but they are also to look forward and seek opportunities to improve their situation and rectify existing wrongs. They are told that while the risks and struggle may be great, the ultimate benefit and reward will be much greater (2:218; 3:142; 4:95-96; 8:74; 9:88-89; 6:110; 29:69).

Those who believed and fled their homes, and strove hard in God’s way with their possessions and their selves are much higher in rank with God. And it is these – they are the triumphant. (9:20)

Life was never meant to be easy. The Qur’an refers to a successful life as an “uphill climb,” a climb that most will avoid.

We certainly have created man to face distress. Does he think that no one has power over him? He will say: I have wasted much wealth. Does he think that no one sees him? Have We not given him two eyes, and a tongue and two lips and pointed out to him the two conspicuous ways? But he attempts not the uphill climb; and what will make you comprehend the uphill climb? [It is] to free a slave, or to feed in a day of hunger an orphan nearly related, or the poor one lying in the dust. Then he is of those who believe and exhort one another to patience and exhort one another to mercy. (90:4-17)

Wishful Thinking

“Why create man?” The angels’ question echoes through our reflections. We can at least attempt a partial explanation based on what we have learned from the Qur’an so far.

It seems that God, in accordance with His attributes, intends to make a creature that can experience His being (His mercy, compassion, love, kindness, beauty, etc.) in an intensely personal way and at a level higher than the other beings known to mankind. The intellect and will that man has been given, together with the strife and struggle that he will surely face on earth, somehow contribute to the development of these individuals, this subset of humanity that will be bound to God by love.

We need to travel on and delve deeper in this direction in order to gain greater insight. But before we do, we should consider the possibility that we may be deluding ourselves. By this I mean that we may have been reading into the Qur’an something that is not really there; we may have been projecting onto the scripture our own personal conflict, one that the Qur’an never insists on explicitly nor even intentionally raises the issue of an ultimate purpose behind the creation of man. Yet here again we meet with the persistently provocative method of the scripture. Just when we are prepared to doubt our first impressions and to revert to the familiar and comforting corner of cynicism from which we have come, the Qur’an reopens the topic.

Those [are believers] who remember God standing and sitting and lying down and reflect upon the creation of the heavens and the earth [and say]: Our Lord, You did not create all this in vain. (3:191)

We have not created the heaven and the earth and whatever is between them in sport. If We wish to take a sport, We could have done it by Ourselves – if We were to do that at all. (21:16-17)

Do you think that We created you purposely and that you will not be returned to Us? The true Sovereign is too exalted above that. (23:115)

We did not create the heavens and the earth and all that is between them, in play. (44:38)

So for us there is no easy escape. The Qur’an apparently will not back out of the challenge. It is up to us to either continue on in this search or to resign and avoid a decisive engagement. Our numbers now are almost surely less than when we started. For those willing to continue, we should consider what would be the next natural step. Since the Qur’an undoubtedly claims that life has a reason and since, as we observed, it has to do with the nurturing of a certain relationship between God and man, it would seem quite appropriate to seek more information about the nature of man and what the Qur’an requires of him as well as about the attributes of God and how mankind is affected by them.

Except Those Who Have Faith and Do Good

The key to success in this life and the hereafter is stated so frequently and formally in the Qur’an that no serious reader can miss it. However, the utter simplicity of the dictum may cause one to disregard it, because it seems to ignore the great questions and complexities of life. The Qur’an maintains that only “those who have faith and do good” (in Arabic: allathina aaminu wa ’amilu al saalihaat) will benefit from their earthly lives (2:25; 2:82; 2:277; 4:57; 4:122; 5:9; 7:42; 10:9; 11:23; 13:29; 14:23; 18:2; 18:88; 8:107; 19:60; 19:96; 20:75; 20:82; 20:112; 21:94; 22:14; 22:23; 2:50; 22:56; 24:55; 25:70-71; 26:67; 28:80; 29:7; 29:9; 29:58; 30:15; 30:45; 31:8; 32:19; 34:4; 34:37; 35:7; 38:24; 41:8; 42:22; 42:23; 2:26; 45:21; 45:30; 47:2; 47:12; 48:29; 64:9; 65:11; 84:25; 85:11; 5:6; 98:7; 103:3). This statement and very similar ones occur so often that it warrants careful analysis.

Wa ’amilu al saalihaat (and do good). The verb ’amila means “to do”, “to act”, “to be active”, “to work”, or “to make”. It implies exertion and effort. Thus the associated noun ’amal (pl. a’maal) means “action”, “activity”, “work” or “labor”, as in the verse, “I waste not the labor (’amala) of any that labors (’amilin)” (3: 195). The noun al saalihaat is the plural of saalih, which means “a good or righteous act”. But this definition does not bring out its full meaning. The verbs salaha and aslaha, which come from the same Arabic root, mean “to act rightly and properly”, “to put things in order”, “to restore”, “to reconcile”, and “to make or foster peace”. Hence the noun sulh means “peace”, “reconciliation”, “settlement” and “compromise”. Therefore, the phrase ’amilu al saalihaat (“do good”) refers to those who persist in striving to set things right; to restore harmony, peace, and balance.

From the Qur’an’s many exhortations and its descriptions of the acts and types of individuals loved by God, it is not difficult to compose a partial list of “good works”. Not unexpectedly, it will consist of those acts and attributes that are universally recognized as virtuous. One should show compassion (2:83; 2:215; 69:34), be merciful (90:17), forgive others (42:37; 45:14; 64:14), be just (4:58; 6:152; 6:90), protect the weak (4:127; 6:152), defend the oppressed (4:75), seek knowledge and wisdom (20:114; 22:54), be generous (2:177; 23:60; 0:39), truthful (3:17; 33:24; 33:35; 49:15), kind (4:36), and peaceful (8:61; 25:63; 47:35), and love others (19:86).

Truly those who believe and do good will the Most Merciful endow with love and to this end have We made this easy to understand in your own tongue, so that you might convey a glad tiding to the God-conscious and warn those given to contention. (19:86)

One should teach and encourage others to practice these virtues (90:17; 103:3) and, by implication, learn and grow in them as well. The stories of the prophets have God’s messengers bidding their communities and families to adopt such ethics, although many of them remain contemptuous.

It is not surprising that the Qur’an upholds the so-called golden rule. Many do feel that it is better to give than to receive, to be truthful rather than to live a lie, to love rather than to hate, to be compassionate rather than to ignore the suffering of others, for such experiences give life depth and beauty. I believe that in the winters of our lives, our past worldly or material achievements will seem less important to us than the relationships we had, loves and friendships that we shared, and times we spent giving of ourselves and doing good to others. In the end, according to the Qur’an, these are what endure.

But the things that endure – the good deeds – are, with your Lord, better in reward and better in hope. (18:46)

And God increases the guided in guidance. And the deeds that endure – the good deeds – are, with your Lord, better in reward and yield better returns. (19:76)

These are the themes of songs, poems, novels, plays, and films not only because of their sentimental appeal, but because they are part of our collective human experience and wisdom. Some would say that life is really not about taking, but about giving and sharing, and that this is what gives life meaning and purpose. The Muslim, however, would not fully agree. If human intellectual, moral, and emotional evolution was the sole purpose of life, then belief in God might be helpful, but not entirely necessary, for a humanistic ideology may suffice. But the Qur’an does not state that the successful in life are only “those who do good”; rather, they are only those who unite faith with righteous living, those who “have faith and do good”.

Illa-l lathina aamanu (except those who believe). The verb aamana means “to be faithful”, “to trust”, “to have confidence in”, and “to believe in”. It is derived from the Arabic root, AMN, which is associated with the ideas of safety, security, and peace. Thus amina means “to be secure”, “to feel safe”, “to trust”; amn means “safety”, “peace”, “protection”; amaan means “safety”, “shelter”, “peace”, and “security”. The translation of aaminu as “believe” is somewhat misleading, because in modern times it is usually used in the sense of “to hold an opinion” or “to accept a proposition or statement as true”. The Arabic word has stronger emotional and psychological content, for “those who believe” implies more than an acceptance of an idea; it connotes a personal relationship and commitment and describes those who find security, peace, and protection in God and who are in turn faithfully committed to Him.

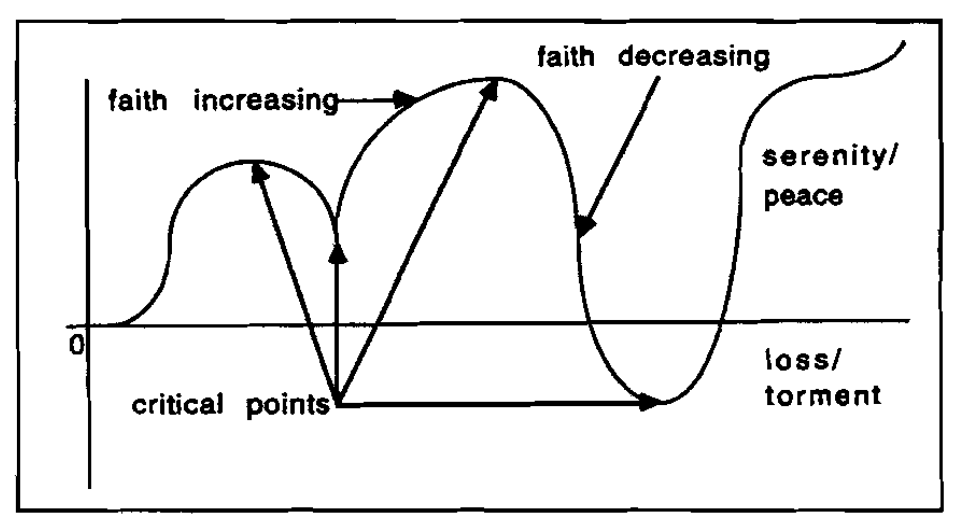

Like the phrase we are analyzing, the Qur’an maintains the utter indivisibility between faith and good works. The mention of the first is almost always conjoined to the second. Faith should inspire righteous deeds, which, in turn, should nurture a more profound experience of faith, which should incline one to greater acts of goodness, and so on, with each a function of the other, rising in a continuous increase. From this viewpoint, all of our endeavors acquire a potential unity of purpose: ritualistic, spiritual, humanitarian, and worldly activity are all brought into the domain of worship. Good deeds become simultaneously God-directed and man-directed acts. For example, the spending of one’s substance on others becomes an expression of one’s love of God.

But piety is to … spend of your substance out of love for Him. (2:177)

Hence the relationship between God and man is inextricably bound to man’s relationship with fellow man.

Repeatedly, we come upon the Qur’anic exhortation, “Establish salah [ritual prayers] and pay zakah [the annual financial tax].” We normally think of the first as God-directed and the second as community, and hence man, directed. While this may be so, the line between them is extremely faint in Islam, for both are ritual obligations and both require and contribute to a high level of community discipline and cohesion.

Many a non-Muslim has been impressed with the synchronous, almost military, precision of a Muslim congregation in prayer. At the call to the prayer, the congregation quickly arranges itself in tight formation, with no one possessing a fixed or privileged position, so that even the prayer leader is frequently elected on the spot from those present. In this way, the prayer becomes not only a powerful spiritual exercise, but, secondarily, also trains the community in leadership, organization, cooperation, equality, and brotherhood. The physical and hygienic advantages of preparing for and performing the ritual prayer have also been noted frequently by outsiders. This is not to say that Muslims would list these gains as the primary benefits of prayer – indeed they would not – but it does exemplify how the spiritual and worldly intersect and complement each other in Islam.

The ritual of zakah illustrates the same point but from the reverse angle. It is the yearly tax – something like a social security tax – on a Muslim’s wealth, which is distributed to the poor and needy and others as stipulated in the Qur’an (9:60). The social concerns behind this tax are obvious, but the Qur’an underlines its personal and spiritual sides as well. The word zakah, which means “alms” or “charity”, is associated with the Arabic verbs zakka and tazakka, which mean “to purify” or “to cleanse”. Muslims have long understood that through its payment one may attain to higher levels of spiritual purity. This is not a coincidental or forced association, because the Qur’an clearly makes the connection between almsgiving and self-purification.

So take of their wealth alms, so that you might purify (tuzakkeehim) and cleanse them. (9:103)

But the most devoted to God shall be removed far from it: those who spend their wealth to purify (yatazakka) themselves. (92:18)

The Qur’an’s recurring summons to establish salah and pay zakah is indicative of its general attitude towards faith and good deeds: They are interconnected and mutually enriching. The ultimate goal is to perfect harmony between both types of activities, as each is indispensable to our complete development. Thus, giving of oneself strengthens the experience of faith, or, as the Qur’an says, spending in God’s way and doing good brings one nearer to God and His mercy.

And some of the desert Arabs are of those who believe in God and the Last Day and consider what they spend as bringing them nearer to God and obtaining the prayers of the Messenger. Truly they bring them nearer [to Him]; God will bring them into His mercy. (9:99)

And it is not your wealth nor your children that bring you near to Us in degree, but only those who believe and do good, for such is a double reward for what they do, and they are secure in the highest places. (34:37)

The vision of the “face of God” refers to the intense mystical encounter obtained in the hereafter by those who attain the highest levels of spirituality and goodness. Here too the Qur’an connects this divine vision with our concern and responsibility towards others.

So give what is due to kindred, the needy and the wayfarer. That is best for those who seek the face of God, and it is these, they are the successful. (30:39)

As these verses show, virtuous acts augment faith and spirituality. More than acceptance of dogma or a state of spiritual consciousness, faith in Islam is comprehensive, an integrated outlook and way of living that incorporates all aspects of human nature and that increases with the level of giving and self-sacrifice.

By no means shall you attain piety unless you give of that which you love. And whatever you give, God surely knows it. (3:92)

Those who responded to the call of God and the Messenger after misfortune had befallen them – for such among them who do good and refrain from wrong is a great reward. Men said to them: surely people have gathered against you, so fear them; but this increased them in faith, and they said: God is sufficient for us and He is an excellent guardian. (3:172-173)

When the believers saw the confederate forces, they said: “This is what God and His messenger had promised us, and God and His messenger told us what was true.” And it only increased them in faith and in submission. (33:22)

Conversely, the spiritual experiences of faith should intensify one’s commitment to goodness:

And those who give what they give while their hearts are full of awe that to their Lord they must return – These hasten to every good work and they are foremost in them. (23:60-61)

The believers are those who, when God is mentioned, feel a tremor in their hearts, and when His messages are recited to them they increase them in faith, and in their Lord do they trust; who keep up prayer and spend out of what We have given them. These, they are the believers in truth. (82:3-4)

Doctrine, ethics, and spirituality overlap to such a degree in the Qur’an, that they are frequently interwoven in its definitions of piety and belief.

Piety is not that you turn your faces towards the East or West, but pious is the one who has faith in God, and the Last Day, and the angels, and the scripture, and the messengers, and gives away wealth out of love for Him to the near of kin and the orphans and the needy and the wayfarer and to those who ask and to set slaves free and keeps up prayer and practices regular charity; and keep their promises when they make a promise and are steadfast in [times of] calamity, hardship and peril. These are they who are true [in faith]. (2:177)

The sacrificial camels We have made for you as among the symbols of God: in them is (much) good for you: then pronounce the name of God over them as they line up (for sacrifice). When they are down on their sides (after slaughter), eat thereof and feed such as those who live in contentment and such as beg in humility: thus have We made animals subject to you that you may be grateful. It is not their meat nor their blood that reaches God: It is your piety that reaches Him. (22:36-37)

Prosperous are the believers, who are humble in their prayers, and who shun what is vain, and who are active in deeds of charity, and who restrain their sexual passions – except with those joined to them in marriage, or whom their right hands possess, for such are free from blame, but whoever seeks to go beyond that, such are transgressors – those who faithfully observe their trusts and covenants, and who guard their prayers. (23:1-9)

The second passage refers to the day of sacrifice at the annual pilgrimage to Makkah. The pilgrimage is one of Islam’s five ritual “pillars” and it is, even today, perhaps the most physically demanding of all of them. It is stunning in its religious imagery, emotion, and drama. And yet, here too, the Qur’an interconnects its social and spiritual benefits.

Non-Muslims are often surprised by the spirit of optimism and celebration that pervades Muslim rituals, especially during Ramadan (the month of fasting) and the pilgrimage, which they assume are performed mostly as atonement for past sins. Muslims, however, perceive their rituals positively – as spiritually and socially progressive. They understand them to be a challenge and an opportunity, as is life itself.

Islam means “surrender” or “submission”, a giving up of resistance, an acquiescence to God’s will, to His created order and to one’s true nature. It is a lifelong endeavor and trial, an endless road that opens to boundless growth. It is a continuous pursuit that leads to ever greater degrees of peace and bliss through nearness to God. It engages all human faculties and its terms are unconditional. It seeks a voluntary commitment of body and mind, heart and soul. Its comprehensives may be brought to light by examining one of the great questions of Christianity: “Is salvation obtained by faith or good works?”

First, the question needs to be rephrased, because it is unnatural to Muslims. Islam has known nothing similar to Christianity’s soteriology. If a Muslim is asked: “How do you know you are saved?” he or she will likely respond: “From what or from whom?” Earthly life for Muslims is an opportunity, a challenge, a trial, not a punishment from which one must be rescued. In the Qur’an, all creation, knowingly or unknowingly, serves God’s ultimate purposes. Thus it would not be obvious to a Muslim that we needed to be saved from some entity. Even Satan is stripped of his power in the Qur’an and reduced to the function of eternal tempter, a catalyst for ethical decision making and, hence, for moral and spiritual development. If anything, Muslims feel that they may need to be saved from themselves, from their own forgetfulness and unresponsiveness to God’s many signs.

In a Muslim context, it would be more natural to ask, “How does one achieve success in this life: through faith or good works?” In consideration of what we have already observed, the answer becomes immediately obvious: both are essential. Otherwise, human existence would not make sense and much of life would be superfluous. For the Muslim, such a question would be analogous to asking, “What element in water – hydrogen or oxygen – is necessary to quench one’s thirst?”

Before considering what the Qur’an tells us about God, let us recapitulate. The Qur’an claims that man’s earthly life is not a punishment and that it does not satisfy some whim of its creator. Rather, it is a stage in God’s creative plan. Mankind has been endowed with a uniquely complex nature with contrary inclinations. Through the use of his/her faculties (intellectual, volitional, spiritual, moral, etc.) and the trials he or she is guaranteed to face, an individual will either grow in his or her relationship with God – or as the Qur’an says “in nearness to God” – or squander himself or herself in misdirected pursuits. The Qur’an asserts that this earthly life will indeed produce a segment of humanity that will experience and share in God’s love; these are called in the Qur’an Muslimun (Muslims; literally, “those who surrender”), for they strive to submit themselves – heart, mind, body and soul – to this relationship. They are those who find peace, security, and trust in God and who do good and strive to set things right. To better understand how the lives we lead facilitate closer communion with God, we turn now to God in the Qur’an.

The Most Beautiful Names

The Qur’an presents two obverse portraits of God and His activity. On the one hand, He is transcendent and unfathomable. He is “sublimely exalted above anything that men may devise by way of definition” (6:100); “there is nothing like unto Him” (42:11); and “nothing can be compared to Him” (112:4). These statements warn of the limitations and pitfalls in using human language to describe God, especially such expressions as are commonly used to describe human nature and behavior, for man’s tendency to literalize religious symbolism often leads to the fabrication of misguiding images of God. Nevertheless, the above statements serve only as cautions in the Qur’an, since it too, of necessity, contains such comparative descriptions. If we are to grow in intimacy with God, then we need to know Him, however approximately, in order to relate to Him, and toward this end speech is an obvious and indispensable tool.

Thus, in addition to declarations of God’s complete incomparability, we find His various attributes mentioned on almost every page. Often used to punctuate passages, they occur typically in simple dual attributive statements, such as, “God is the Forgiving, the Compassionate” (4:129), “He is the All-Mighty, the Compassionate” (26:68), “God is the Hearing, the Seeing” (17:1). Collectively, the Qur’an refers to these titles as al asmaa al husnaa, God’s “most beautiful names” (7:180; 17:110; 20:8; 59:24).

Say: Call upon God, or call upon the Merciful, by which ever you call, to Him belong the most beautiful names. (17:110)

God! There is no God but He. To Him belong the most beautiful names. (20:8)

He is God, other than whom there is no other god. He knows the unseen and the seen. He is the Merciful, The Compassionate. He is God, other than whom there is no other God; the Sovereign, the Holy One, the Source of Peace, the Keeper of Faith, the Guardian, the Exalted in Might, the Irresistible, the Supreme. Glory to God! Above what they ascribe to Him. He is God, the Creator, the Evolver, the Fashioner. To Him belong the most beautiful names. Whatever is in the heavens and on earth glorifies Him and He is exalted in Might, the Wise. (59:23-24)

The Divine Names are a ubiquitous element of Muslim daily life. They are invoked at both the inception and completion of even the most common tasks, appear in persons’ names in the form of Servant of the Merciful, Servant of the Forgiving, Servant of the Loving, etc., cried out in moments of great joy and sorrow, murmured repeatedly at the completion of ritual prayers, and chanted rhythmically in unison on various occasions. Because Muslims insert them into conversations so frequently and effortlessly, some outsiders have accused Muslims of empty formalism. But this reflects a lack of understanding, for the truth is that the Divine Names play such an integral role in the lives of the faithful that their use is entirely natural and uninhibited.

The Divine Names are, for Muslims, a means of turning towards God’s infinite radiance. Through their recollection, believers attempt to unveil and reorient their souls towards the ultimate source of all. A knowledge of them is essential if one is to comprehend the relationship between God and man as conceived in the Qur’an and as experienced by Muslims.